“While there are few straight lines in nature, there are many definite and powerful edges—various ecotones, watershed divides, climatic zones, fault-lines and scarps. Careful attention should be given to such beginnings and endings, for these dramatic turnings in the earth serve as clear and powerful articulations of diversity.”

– David McCloskey – On Bioregional Boundaries

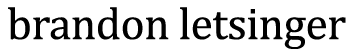

Bioregions are the natural countries of the planet, containing within them many nations, inhabitants, watersheds and ecosystems.

Boundaries in of themselves are not good or bad. They define the edges of things. Places where different zones meet and collide. Unlike many borders in our world today, bioregional boundaries are not an abstraction given to a place. Rather they are real, physical features which can be seen, felt, measured, and tested.

They are created through three different elements melding together:

- Hard Boundaries:

The defining features of a bioregion are often hard, often fractured edges. They include geology, topology, morphology – primal forces including: plate tectonics, subduction zones, upthrust zones, fracture zones, scarps, fault lines, volcanoes, mountain ranges. From hard boundaries, we usually get the external boundaries of a bioregion.

From these features emerge how the area is acted upon by other elements – rainfall patterns, watersheds, wind, sediment, erosion patterns. - Soft / Fuzzy Boundaries:

From these ‘hard boundaries’ emerge softer ones. A bioregional layering that creates the ecoregions, biomes, ecosystems and probably the things we think of when we think of home. Our rivers, forests, streams, soil, animals, plant life. Some of these borders will still have hard edges, and others will blend, from one ecotone to another. From these sometimes softer borders, we often define our internal boundaries and ecoregions of a bioregion. - Human Culture:

Lastly, human culture – how we live in a place and our impact on it – is an incredibly important part of mapping our bioregions. As of the 1990’s, humans are now the second largest mover of dirt in the world, behind that of water, and ahead of wind. One of the the most important things that Peter Berg did when he adapted the term bioregion in 1971 was to include human beings as part of their ecosystem rather than removed from it.

Human ways of living are important, because regardless of arbitrary boundaries, how climate change will impact an area, or fires burn, flooding happens, native ecosystems, plants, fish or animals recover, water quality and river health regenerates, drought and soil health measured – are all bioregional questions, and will each need a bioregional answer.

Together, with these three layers, the framework of a bioregion is the largest physical connection of scale that makes sense, and the furthest extent of it’s watersheds – because ultimately, every person and community living within a watershed must be able to substantively weigh in and contribute to those discussions which might impact them the most.

[…] Bioregional Boundaries […]